Thanks to the support of a Penelope Biggs Travel Award and the Department of Classics, Lecturer Justin Meyer traveled to Munich and Augsburg this spring to conduct research at the Bavarian State Library and the Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg. Despite an illness that interrupted the final week of his trip, Meyer reports a highly productive research experience centered on a remarkable 15th-century manuscript.

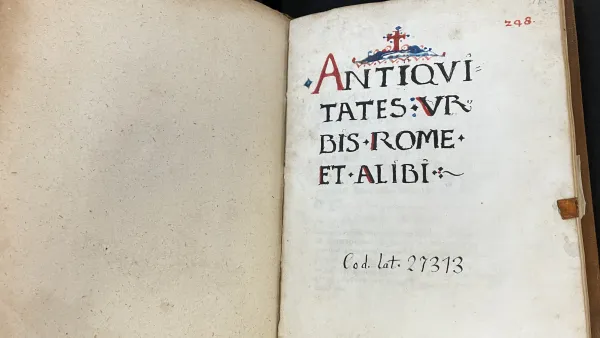

The focus of Meyer’s research was Hartmann Schedel’s Liber Epigraphicus, a manuscript Schedel titled Antiquitates Urbis Rome et Alibi. The manuscript is a rich compilation of hand-drawn illustrations and Latin inscriptions, documenting one of the earliest known efforts by German humanists to study and preserve Roman material culture. Among its contents are sketches of Roman monuments—such as a triumphal arch Meyer identifies as likely the Arch of Constantine—and numerous transcribed inscriptions, including that of P. Platius Pulcher (CIL XIV 3607).

Schedel’s interest in inscriptions mirrors a broader 15th-century humanist trend, and his work later caught the attention of Theodor Mommsen, the founder of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL). Mommsen used the Liber Epigraphicus extensively and even signed his name in the volume, a mark of scholarly engagement that will be included in an upcoming digitization.

A long-standing scholarly puzzle around the Liber Epigraphicus is the uncertainty of its date of composition. Originally part of a much larger collected volume, the manuscript was removed and rebound in the 19th century. Interestingly, the current binding includes a copy of the Bullettino dell’Istituto di Corrispondenza Archeologica from July 1884, containing notes on one of the Liber’s inscriptions. Meyer’s tentative theory is that the manuscript was rebound in the 1880s—perhaps by Mommsen himself—to facilitate easier consultation for the CIL. Given the size of many of Schedel’s volumes (often exceeding 600 pages), this would have been a logical step.

In addition, Meyer has identified several inscriptions in the Liber that appear in only one other known source, dated to 1502, which may suggest that the manuscript was compiled later than currently assumed. Recovering information about the original volume and any associated texts may help resolve this dating question.

One of the most exciting outcomes of Meyer’s trip is that the Liber Epigraphicus is now in the process of being digitized in high resolution by the Bavarian State Library. The resulting open-access digital edition will replace the outdated microfiche images currently available and will make the full manuscript accessible online in full color for the first time. Meyer plans to share the link with the department as soon as the digitization is complete.

The Department congratulates Justin Meyer on this valuable contribution to the study of early modern engagement with antiquity and thanks the Biggs Family for their continued support of faculty and student research in Classics.